Painter, sculptor, printmaker, photographer, and theater artist. His declared intention to “act” in the “gap” between art and life, as he put it in 1959, succinctly characterized his contribution to art history. In the 1950s he broadened abstract expressionism to include non-art elements. His recognition of the aesthetic potential of ordinary objects stimulated the development of pop art, while his interest in incorporating in the art object signs of its own making opened the way for process art. Other aspects of his work resonated in minimal, conceptual, and performance art. However, his multifarious and inclusive approach always remained beyond the reach of any single art movement. He also facilitated the use of photography as an unremarked component of fine art and fostered acceptance of hybrid genres of all sorts. Over time, he increasingly became a sort of reporter, witnessing and assembling representations of the newsworthy events and ordinary minutiae of his time. As a generator of ideas, he numbered among indispensable figures of late twentieth-century art.

Born in Port Arthur, Texas, Milton Ernest Rauschenberg later officially changed his name to Robert. Not long after he enrolled at the University of Texas to study pharmacy, he was drafted. Trained in the U.S. Navy as a neuropsychiatric technician, he spent his tour of duty in California. In 1947 he began his professional art training at the Kansas City Art Institute. In March 1948 he arrived in Paris, where he studied without much enthusiasm at the Académie Julian. That fall he enrolled at Black Mountain College to study with Josef Albers. After a year, he moved to New York and until 1952 continued his studies at the Art Students League, where Morris Kantor and Vaclav Vytlacil numbered among his teachers. In the spring of 1951 Betty Parsons staged his first one-person show at her gallery, as simultaneously his work appeared in the abstract expressionists’ “Ninth Street Show.” He also met John Cage that season before returning in the summer to Black Mountain, as he did again the following year. During those sessions, Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind stimulated his already growing interest in photography as an art form, while Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Jack Tworkov encouraged his painting. In 1952 he participated there in a Cage event that anticipated happenings. That fall he departed for Europe with Cy Twombly to travel and work until the next spring mostly in Italy but also in North Africa and Spain.

This rich mix of early experiences soon came to fruition as Rauschenberg embarked upon original and influential work in the mid-1950s. Until this time, he had worked on several series of monochrome paintings, as well as experiments in photography, collage, and assemblage. In retrospect, it is apparent that one particularly provocative work not only deliberately challenged New York’s advanced taste but also announced his intention to revamp the field. After persuading Willem de Kooning to give him a drawing, Rauschenberg laboriously erased it and retitled the resulting spectral image Erased de Kooning Drawing (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1953). At once a salute to the older artist’s stature and an anti-art, dadaist provocation, it also alerted contemporaries to the potential of the conceptual gesture. Early in 1954 Rauschenberg met Jasper Johns, who quickly became a close friend. For a while they worked together decorating department store display windows for the legendary designer Gene Moore, and off and on they were lovers, but most significantly they spurred each other to new levels of creative achievement during the next few years. In addition to each other’s criticism, both responded to Cage’s ideas particularly and, from a distance, to Marcel Duchamp‘s. Rauschenberg had already demonstrated a sensuous attraction to materials in varied cobbled-together works, but in the mid-1950s he began to bring large objects into conjunction with painting to create what he called “combines.” Neither painting nor sculpture exactly, most of them hang on the wall but incorporate all manner of accessories, generally commonplace objects or the sort of detritus that found its way into contemporary junk sculpture. An early example, Rebus (Museum of Modern Art, 1955), collages together newspaper comic strips, a small reproduction of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, news photos, and children’s art within a visual catalogue of recent painting techniques. In its messy juxtapositions of high and low culture, its unresolved visual and thematic tensions, and its reprise of art-making techniques, it prefigured much that would come in Rauschenberg’s career. However, the most notorious combine approximates sculpture. Monogram (Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1955–59) features on a painted canvas base a stuffed long-horned angora goat, with paint-daubed face and an automobile tire around its middle.

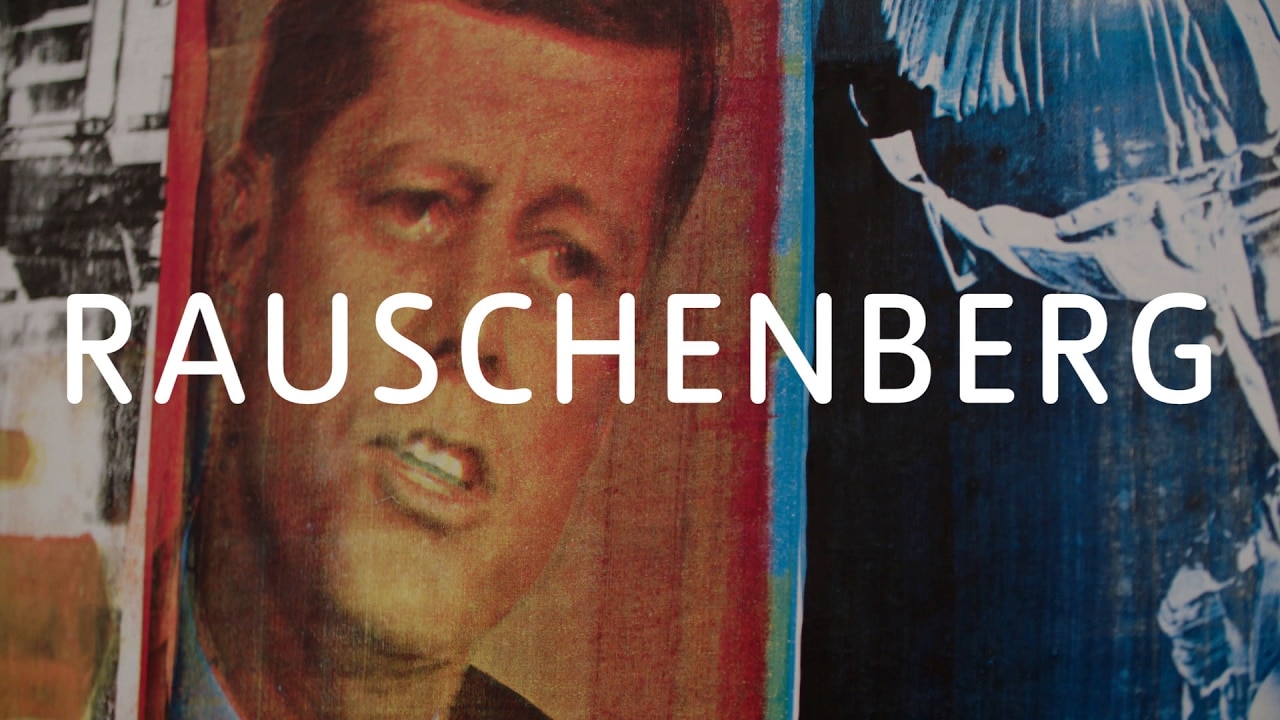

Although the combines failed to sell, they attracted considerable interest in March 1958 when Leo Castelli featured them in his first show devoted to Rauschenberg’s work. In 1959 the artist embarked on a suite of thirty-four drawings inspired by the cantos of Dante’s Inferno (Museum of Modern Art, 1959–60). Using a novel transfer technique, he incorporated borrowed imagery from published illustrations along with his own painted and drawn elements. Free association governed his approach to narrative, giving the individual drawings a dreamlike ambiguity. In 1962, following Andy Warhol‘s example, he began using screen prints to achieve similar effects on canvases. So congenial was this process that within a couple of years he altogether ceased making combines. Subsequently he employed the screen print technique, or variations on it, in thousands of paintings and in an extensive engagement with printmaking, primarily lithography, begun also in 1962. With the screen print process, he was able to embed in his paintings photographic images of all sorts, particularly news pictures that registered the increasing importance of mass-media communication in contemporary life. In a leap to worldwide celebrity, in 1964 Rauschenberg won the top prize for painting at the Venice Biennale. However, in the immediate aftermath of this honor, he almost abandoned painting for several years. Also in 1964 he ended more than a decade of intense collaboration with choreographer Merce Cunningham and instead expanded his involvement with other sorts of staged theatrical events. He also made interactive works that responded to the viewers’ presence and sometimes included sound elements. In 1966 he spearheaded the formation of Experiments in Art and Technology to promote interaction between artists and scientists.

By the end of the 1960s, Rauschenberg had renewed his interest in two-dimensional media, to which he now brought a new elegance and breadth of vision. Among the most appealing works of the 1970s, the Hoarfrost series (1974–76) consists of gauzelike textiles imprinted with imagery and hung loosely in lyrical, layered arrangements. Extending and amplifying the artist’s interest in the social purposes of art, the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, initiated to stimulate world understanding through visual communication, consumed nearly all his time from 1984 until 1991, as well as millions of his own dollars. He traveled to ten countries for the express purpose of working with local artists, staged exhibitions in their home countries, and produced a huge, multireferential final display. From 1970 Rauschenberg died on his longtime Captiva Island home, off the Florida Gulf Coast. Despite health problems during his final years, including a stroke in 2002 that paralyzed his right side, with assistance he continues working productively. In 2005 he exhibited works from Scenarios, a new series of fresh and lucid digitized pigment transfers, emphasizing, as usual, his fascination with looking at the world.

Born in New York, his son Christopher Rauschenberg (1951– ) is a photographer based in Portland, Oregon. He earned a B.A. in photography at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. Since undertaking a 1997–98 project to re-photograph Eugène Atget’s Paris, he has traveled the world, aiming his camera principally at architecture to capture formal qualities inflected by human milieus. He works mostly in subdued color and often combines two or more contiguous images to provide a wider angle of eloquent vision. His mother, painter and printmaker Susan Weil (1930– ), was married to Rauschenberg from 1950 until 1952. She spent her early childhood in New Jersey but later lived in New York, where she studied with Rufino Tamayo and Vytlacil at a private high school. Better educated as an artist than Rauschenberg when they met in Paris during the summer of 1948, she studied along with him at Black Mountain and at the Art Students League. During their years together, they collaborated on a number of works, most notably a series of large blueprint “drawings” made by exposing the light-sensitive paper to record images, usually nude human bodies, placed on top of it. Since then, she has engaged relationships between literary and visual art in interpreting many challenging works, including writings of James Joyce. Recent paintings, some reassembled from fragments, time passing within a context of ordinary daily life. She also creates books and designs sets, particularly for dance performers. She lives in New York.