Camille Pissarro was not treated well by the critics of his time. Some ridiculed his love for green, violet, and blue. Others disliked his radical beliefs.

He was, however, at the beginning of Impressionism, although he did not claim what others denied him anyway – denied him and his companions, all younger than himself but whom he resembled – the credit for discovering it.

Maurice Denis has described “the warm, dark, golden look on his brown face – Jewish, Spanish, Creole,” adding that in “his soft, caressing voice (he) prophesied the society of the future”.

Camille Pissarro was slow. But we must not forget that he turned Cezanne toward nature, and this was his brief and glorious adventure.

It was he who pointed out “the wheat, the onion, and the apple”. In his work he raised the fresh charm of the countryside, and all the produce that is sold in vegetable markets, to the level of what Ingres had called the painting of history.

Like Millet, but with a secular religious feeling, Pissarro loved flocks of sheep, peasant women pushing barrows of potatoes, flowering cherry and apple trees, willow groves, women bathers in chemises on the banks of rivers. To all this, his frank and healthy approach imparted an urgency of softness and charm.

In our day, with the passage of time, Impressionism has lost the surprise of novelty. But the works of Pissarro take on an unexpected importance, savouring as they do of the earth and radiating an infinite love of nature.

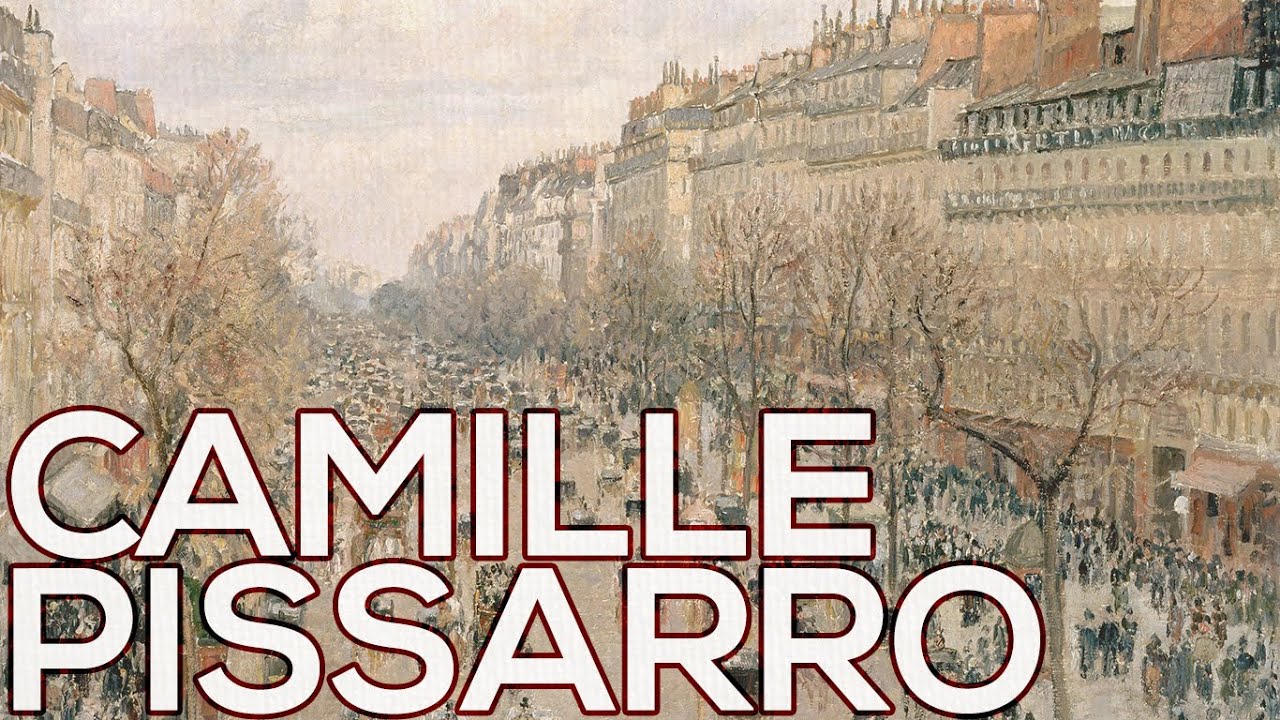

This intimate understanding of the countryside alternates in Pissarro with a passion for Paris, which inspired his views of the boulevards, of the Place du Theatre Francais, of the Pont Neuf, and those of the Quai Henri IV, where, a bearded patriarch, the painter ended his days.

The Impressionist landscape painters were described by Armand Silvestre in 1873 in words that are still valid: “M. Monet is the most able and the most daring, M. Sisley the most harmonious and the most timid, M. Pissarro the most real and the most natural”.

The Little Country Maid, Oil on canvas, 1882

Whatever his subject, Pissarro was very consistent in his Impressionist manner of dividing color to give the vibration of light and the distribution of broken touches of rich substance throughout. This picture provides a harmonious scheme for a work of perhaps lesser interest as an example of domestic genre.

In 1882 Pissarro was extending his range of themes after long confining his efforts mainly to landscape. The little servant girl of the title is at work in a room in Pissarro’s house at Osny, near Pontoise, where he worked with Gauguin. The child at the table (painted more vividly than the maid) is presumed to have been Pissarro’s forth son, Ludovic Rodolphe, who was to become known as a painter under the name of Ludovic-Rodo.

Somewhat surprisingly, this gentle canvas was exhibited in London in 1913 in the Post-Impressionist and Futurist exhibition at the Dore Galleries. But in its gentleness there is something of the disquiet of the artist, ever travelling rather than arriving, and also that humility of devotion to his art in which the most fastidious of Pissarro’s artist contemporaries respected a quality of greatness.