This short Vincent van Gogh biography reveals how he shot himself in 1890, at the age of thirty-seven, and ended one of the shortest, most dramatic and brilliant careers of Impressionist art.

In the span of less than ten years he created an unforgettable record, in countless paintings, of the inner drama of his life and of a passionate , uncompromising search for beauty. His work did much to revolutionize the art of the last century, enriching it with a new emotionalism and expressive power.

“The world only concerns me insofar as I feel a certain debt and duty towards it because I have walked on that earth for thirty years, and, out of gratitude want to leave some souvenir in the shape of drawings or pictures – not made to please a certain tendency in art, but to express a sincere human feeling”.

In July, 1880, just ten years before his life ended, the Vincent van Gogh biography started when he wrote to his brother Theo of his decision to become a painter. He was twenty-seven, had unsuccessfully tried to become a picture dealer, schoolmaster, bookseller, and evangelist, and had suffered much anguished doubt that he was good for anything at all.

To his puritan family, who believed in the close connection of work and morality, he seemed an idler and a non-conforming eccentric. Actually he was a man with a calling, but still uncertain of what that calling was.

Vincent van Gogh the painter did not break with his own past. The dramatic single events of Van Gogh’s career, in which he seems at the mercy of outside forces or uncontrollable factors within himself, must never obscure for us the strength of the steadfast determination by which he set his course.

The zeal, the conviction remained the same. He was not a success as a picture dealer because he tried to alter the taste of his clients through argument; as an evangelist he had been too wholehearted and fundamental a Samaritan, carrying his gospel into immediate practice.

He was a dedicated and partisan artist.

He had admired compassion in literature (Shakespeare, Dickens, Hugo, and Harriet Beecher Stowe) and in art (Rembrandt, Israels, Daumier, and Millet). He was a compassionate painter. The love he had thrice offered to women and which had been rejected he poured out in his pictures. He had been aghast at the misery of the London slums and the mining fields of Belgium. He was himself “eternally” poor and found in working people one of his great subjects of inspiration.

He reached his decision to be an artist slowly and painfully, and now he was determined to work through the “invisible iron wall that seems to stand between what one feels and what one can do”, to “undermine that wall and file through it slowly and patiently” in the knowledge that “great things are not something accidental but must certainly be willed”.

Van Gogh, then, was a painter for only a decade. His mature work was produced in even fewer years, for preparation was needed. First Brussels, visiting the museum, studying anatomy and perspective; then several months at home, ending in an unhappy love affair and misunderstandings with his father; then followed nearly two years at The Hague, three months in the desolate north country region in Holland, and another year with his family; then three months in Antwerp, and in February, 1886, the decisive impulse to join his brother Theo in Paris.

His subjects during this time were still life, landscape, and his beloved peasants. He painted a series of portrait heads, another of weavers at their looms, and The Potato Eaters. His palette was dark, based on his native Rembrandt tradition and on Millet and Corot, and he endowed his figures with a coarse but sympathetic dignity.

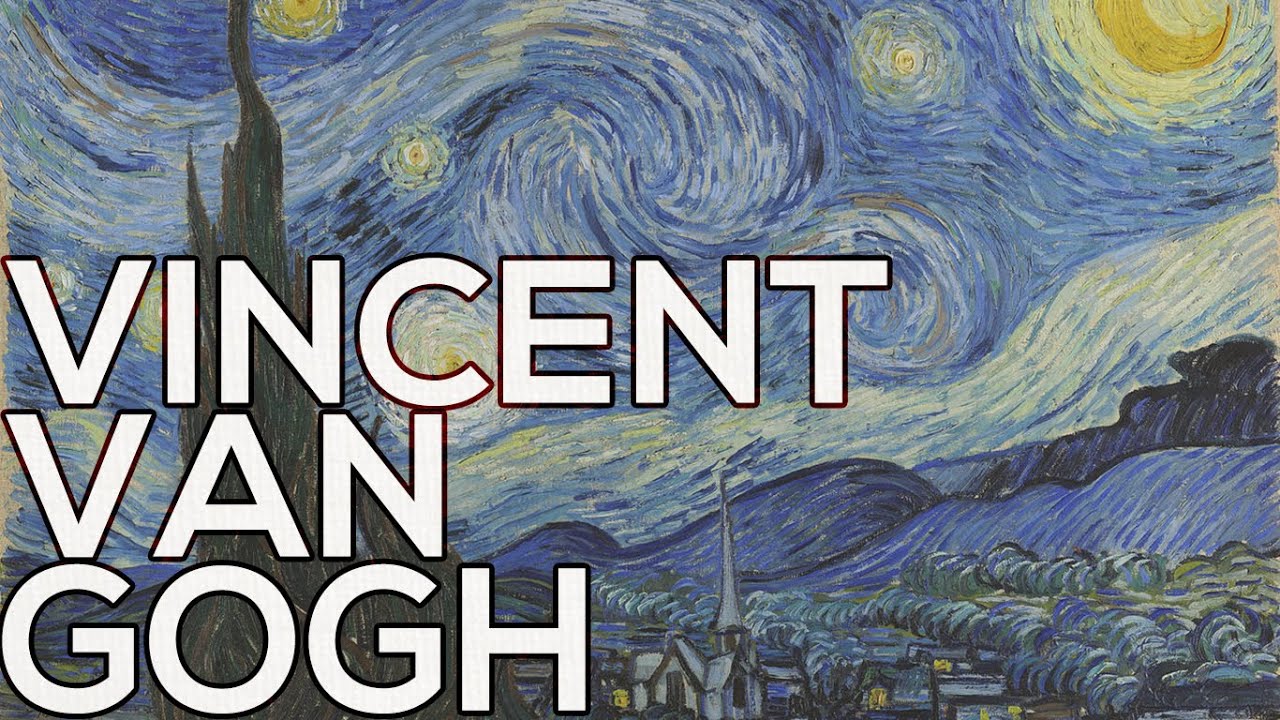

Vincent Van Gogh Biography

In Paris the great revelation was the Impressionists, with their rainbow colors and their broad, broken brush strokes. He had been prepared for this by a study of Delacroix and his Antwerp enthusiasm for Rubens. But now his palette is transformed and becomes clear and light.

In Paris he discovers the Japanese print, which inspires him to a new boldness of design. He comes to know Toulouse-Lautrec, Pissarro, Degas, Seurat, Signac, and Gauguin. His canvases hang alongside theirs in the smaller dealers’ shops. Like them he paints the Seine, the boulevards, the heights of Montmartre, the flag-decked streets on Bastille Day. But his work has a force and directness of attack that is all his own.

And then in February, 1888, just two years after his arrival in Paris, Van Gogh left for the south of France. There, in the town of Arles, he entered upon the final, most productive period of his life. He was greeted by snow, but soon came the southern spring and the southern sun, revealing to this northerner a sudden glory of color and bursting forth of vernal growth that prompted him to a tremendous artistic fecundity.

As always he was without money, living entirely on the generosity of his brother Theo; yet he was full of optimism. He found quarters and friends among the citizens of Arles, and invited Gauguin down to begin his cooperative “atelier of the future”. He painted without letup in his room, in the fields in the hot sun, at night in the cafes, turning out pictures with rapidity, clarity of vision, and assurance.

His letters to his brother were now resumed, and in them we can follow almost day by day the details of Vincent’s life: the nagging worry about money, never having enough, always trying to spend less; the constant, but constantly disappointed, hope that his pictures will sell; nevertheless, his faith in the work he and his brother are doing together – because only Theo’s support makes his painting possible; he discusses his insight into the essential character of his themes and his desire for expression through color.

This correspondence with his brother, together with the letters to his fellow-artists (Van Rappard, Emile Bernard, Gauguin), is one of the great documents of artist creation, a testimony to Van Gogh’s fixity of purpose.

The first of Van Gogh’s attacks of illness (sometimes diagnosed as epilepsy but still uncertain) occurred on the day before Christmas, 1888, while Gauguin was with him in Arles. He was well again very quickly, but in May, 1889, yielding to pressure from his neighbours, he asked to go to the asylum in nearby Saint-Remy. He lived there for a year, and in May, 1890, moved to Auvers, to be near Theo and Theo’s wife and son.

He continued to paint at a feverish pace, but became increasingly melancholy, and in July, 1890, he shot himself. Van Gogh’s suicide was no unpremeditated impulse. He had been conscious of possible insanity for over ten years; for a year and a half there had been increasing interruptions in his work. Faced with the prospect of soon not being able to work at all, he could no longer in conscience be a burden to his brother. To Theo he left his pictures, their joint creation.

Van Gogh’s painting is an art of high intensity, created under pressure by a man of extreme sensitivity, conveying his insight, his immediate feeling, and his intense conviction. But it is also the work of a painter, created with awareness by an artist of extraordinary sensibility, and embodying his knowledge, his considered judgment and his aesthetic understanding.

His art has meaning entirely through his pictorial method. He said, “It was ‘only pictures full of painting’ that I did”. He also said, “I believe in the absolute necessity for a new art of color, of design ,and – of artistic life”.

He created such an art, and in so doing pointed the way to others – inspired by his life and by his work.