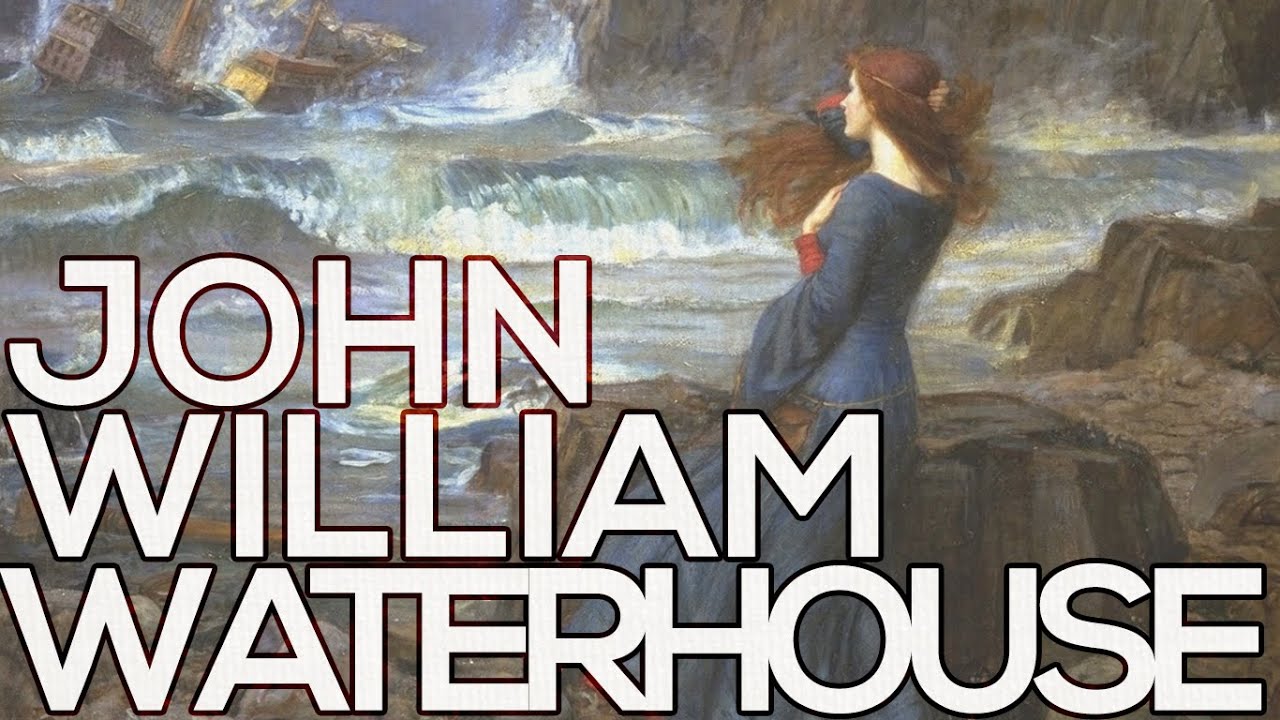

Painter of classical, historical, and literary subjects. Waterhouse was born in 1849 in Rome, where his father worked as a painter. In the 1850s the family returned to England. Before entering the Royal Academy schools in 1870, Waterhouse assisted his father in his studio. His early works were of classical themes in the spirit of Alma-Tadema and Frederic Leighton, and were exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Society of British Artists and the Dudley Gallery. In the late 1870s and the 1880s, Waterhouse made several trips to Italy, where he painted genre scenes. After his marriage in 1883, he took up residence at the Primrose Hill Studios. He was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour in 1883 and resigned in 1889. In 1884, his Royal Academy submission ‘Consulting the Oracle’ brought him favourable reviews; it was purchased by Sir Henry Tate, who also purchased ‘The Lady of Shalott’ from the 1888 Academy exhibition. The latter painting reveals Waterhouse’s growing interest in themes associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly tragic or powerful femmes fatales, as well as plein-air painting. In 1885 he was elected an associate of the Royal Academy and a full member in 1895.

In the mid-1880s Waterhouse began exhibiting with the Grosvenor Gallery and its successor, the New Gallery, as well as provincial exhibitions in Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester. Paintings of this period, such as ‘Mariamne’ (1889), were exhibited widely in England and abroad as part of the international symbolist movement. In the 1890s Waterhouse began to exhibit portraits. In 1901 he moved to St John’s Wood and joined the St John’s Wood Arts Club, a social organization that included Lawrence Alma-Tadema and George Clausen. He also served on the advisory council of the Saint John’s Wood Art School.

Waterhouse continued to paint until his death in 1917. His grave can be found at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Who were the Pre-Raphaelites?

The term Pre-Raphaelite was originally applied to a group of rebellious young English artists who had formed The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, the year of revolution throughout Europe. The Brotherhood only lasted for around five years, but the term ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ lived on and was applied to subsequent painters even though their artistic output did not fully fit the original creed of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Today, it seems the term Pre-Raphaelite is applied to any painting of a mythological or literary subject matter, or even any pretty girl in a flowing dress. Artists such as Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, John William Godward, G.F. Watts, and J.W. Waterhouse are frequently referred to as Pre-Raphaelite. Whether or not this is accurate is a matter for further thought and debate.

Where to view John William Waterhouse’s paintings in person

A list of worldwide museums and galleries with items created by Waterhouse in their permanent collection. The scans shown on this site do not do justice to Waterhouse’s paintings: if you can, try to view a Waterhouse painting in person at one or more of the museums & galleries listed below.

Please note: you’re advised to check ahead that the painting will be on view. For example, sometimes paintings may be in storage, or undergoing restoration or cleaning. If a painting is included in a touring exhibition, and the exhibition does not appear in the column opposite, please send an e-mail with details of the exhibit.

Australia

Adelaide

Art Gallery of South Australia

Circe Invidiosa

The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius

Brisbane

Queensland Art Gallery

The Mystic Wood

Melbourne

National Gallery of Victoria

Ulysses and the Sirens

Sydney

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Diogenes

Canada

Toronto

Art Gallery of Ontario

I am Half-Sick of Shadows, said the Lady of Shalott

England

Burnley

Towneley Hall Art Gallery

Destiny

The Unwelcome Companion

Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth Art Gallery

Study for The Lady of Shalott

The Bouquet

Leeds

City Art Gallery

The Lady of Shalott

Liverpool

Lady Lever Art Gallery

A Tale from the Decameron

The Enchanted Garden

Walker Art Gallery

Echo and Narcissus

London

Leighton House (Hammersmith and Fulham Archives)

Study for Mariana in the South

Royal Academy of Arts

A Mermaid

Tate Britain

Consulting the Oracle

St Eulalia

The Lady of Shalott

The Magic Circle

Victoria and Albert Museum: National Art Library

Letters from the Isidore Spielmann Collection

Victoria and Albert Museum: Print Room

Sketchbooks by J.W. Waterhouse

Manchester

Manchester City Art Galleries

Hylas and the Nymphs

Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Laing Art Gallery

A Flower Stall

Oldham

Oldham Art Gallery

Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses

Oxford

Ashmolean Museum

Two Nymphs – study for Hylas and the Nymphs

Plymouth

City of Plymouth Art Gallery

A Hamadryad

Preston

Harris Museum and Art Gallery

Psyche Opening the Door into Cupid’s Garden

Rochdale

Rochdale Art Gallery

In the Peristyle

Sheffield

Sheffield City Art Galleries

The Artist’s Wife

Germany

Darmstadt

Hessisches Landesmuseum

La Belle Dame Sans Merci

New Zealand

Auckland

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki

Lamia – Keats

Scotland

Aberdeen

Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums

Penelope and the Suitors

Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums

The Danaïdes

Kirkcaldy

Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery

Dolce Far Niente

USA

New York

Dahesh Museum of Art

Dante and Bearice

Pasadena, California

Kelley Gallery

Study for The Love Philtre

Study for The Magic Circle

Study for The Mermaid

Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton University Art Museum

Head of a girl

New Haven, Connecticut

Yale Center for British Art

Study for the Head of Lamia (Miss Muriel Foster)

Wales

Cardiff

National Museum and Gallery of Wales

Fair Rosamund (study)

DEATH OF MR. J.W. WATERHOUSE, R.A.

SPECIAL MEMOIR By SIR CLAUDE PHILLIPS

We regret to announce the death of Mr John William Waterhouse, R.A., who passed away on Saturday, after a long illness, in his 68th year.

There are painters who are known as painters’ painters. In other words, there are artists whose vocation would seem to lie in catering for the great public, and others who use palette and brush from sheer delight in their handicrafts. A modern of the moderns, Mr Waterhouse may be said to have spent his life in experimenting in and perfecting himself in his technique. An eclectic and a devout believer in “art for art’s sake”, the late Academician passed through many stages in the drastic business of educating himself for his life task. A symbolist, to start with, it was impossible for a painter of Mr Waterhouse’s susceptibilities not to be caught in the great naturalistic wave which swept Europe in the early eighties. Thus we find him for a considerable number of years going direct to nature for the inspiration, while, like many other realists, he went the length of posing his models out of doors in the brilliant sunlight. Plein air was the gospel of the movement, and it is certain that Mr Waterhouse succeeded in giving his canvases those vibrating, atmospheric qualities which were the aim of the new prismatic school. It is true that the critics have sought to establish the fact that Mr Waterhouse was at the time influenced by Alma-Tadema. The fact that he interested himself largely in classic subjects no doubt gave colour to the idea that he was at heart a classicist. But this was far from being the case. With the late Academician the manner and not the matter was the thing. For whether he was depicting Miranda, Diogenes, or St Eulalia, it was a colour problem that the artist envisaged his subject. Who, for instance, does not recall the exquisite harmonies of the picture called “The Magic Circle”, where the subtle juxtaposition of mauves and blues recall the happiest inspirations in Persian art? And a dozen other instances might be cited. It was as no cold formalist that Mr Waterhouse envisaged scenes historical. The glamour of the born colourist is to be traced on nearly every canvas to which he put his hand.

John William Waterhouse was born in Rome in the year 1849, and was fortunate in possessing a father who not only devoted his life to art, but encouraged his son to follow his own profession. Thus the boy had leisure to spend his days studying the art treasures accumulated with such profusion in London. The National Gallery, the British Museum, and South Kensington1 became the happy haunts of a student who devised the most original modes of familiarising himself with the work of the great masters. For not only did he model from the antique (it was modelling rather that painting that the youngster essayed in those early days2), but established a system of drawing from memory, which he believed to be of great assistance to him in his after-work. Thus, the picture closely scrutinised and examined in the National Gallery by day would be reproduced from memory at night, a valuable aid to training the retentive qualities of the artistic mind. It was while he was thus engaged in sitting at the feet of the old masters that Mr Waterhouse conceived the idea of painting that first series of allegorical subjects which dwelt with the mysteries of human existence. The artist, indeed, was only twenty-five when he exhibited in the Royal Academy the important picture called “Sleep and his half-brother, Death”, an allegorical work which attracted a good deal of attention in the spring exhibition of 1874. It was a year later that Mr Waterhouse sent “Miranda” to Burlington House3, when he also contributed the canvas called “Whispered Words”. It was not, however, till the year 1876 that Mr Waterhouse was honoured to the extent of being placed on the line4. This coveted privilege was accorded the picture called “After the Dance”, since when the later artist may be said to have been invariably well hung. For, apart from the brilliance of his technique, his shapely way of laying on paint (a subject we have already touched upon), many of Mr Waterhouse’s themes were calculated to attract popular attention. Such, for instance, was the work of 1875, called “A Sick Child Brought into the Temple of Aesculaplus”, and such, again, was undoubtedly the historical picture named “The Remorse of Nero after his Mother’s Death”. A canvas called “The Tibia” was exhibited at Burlington House the same year, while the painter completed the work entitled “La Favorita” the following year.

ELECTED TO THE ACADEMY

Passing to the year 1882, we find Mr Waterhouse engaged on a “Diogenes”, while the ensuing season he exhibited the most important picture he had as yet essayed, “The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius”. Another canvas, called “The Bubbles”, was also seen at Burlington House the same spring, while two years later the artist was elected as Associate of the Royal Academy. In truth Mr Waterhouse would seem to have been working at white heat at this particular time, for we find him tackling in succession such difficult subjects as “Consulting the Oracle” (the oracle Mr Waterhouse presents us with is the far-famed human head of the Teraph), “St Eulalia” and “The Magic Circle”, already alluded to. In the canvas called “St Eulalia” the painter shows us the saint lying in the forum, covered with “the miraculous fall of snow”, which Prudentius describes as “shrouding the body after her martyrdom.” After such a theme the subjects of Ulysses and Circe would naturally present no difficulties to an artist, and accordingly we find Mr Waterhouse busying himself in 1891 with the canvas entitled “Ulysses and the Sirens”. In natural sequence Circe followed, the painter breaking away from the traditional representation of the enchantress turning men into swine to the less hackneyed episode of “Circe Poisoning the Sea”5. A Danaë6 was the output of the same year, the two pictures “A Hamadryad” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci” following in 1893, a year Mr Waterhouse also exhibited a canvas called “A Naiad” at the New Gallery. “The Lady of Shalott” occupied the painter’s attention next, and this subject, with the picture called “Field Flowers” represented his labours for 1894, yet it was neither with Tennyson’s nor Keats’ mystic heroine that Mr Waterhouse reached the high-water mark of his popularity. This was attained with his “St Cecilia”7 in the year 1895, when the Associate was raised to full Academic honours. “Pandora”, another notable success, was the artist’s next venture, and in 1897 we find the Academician exhibiting “Hylas and the Nymphs” at Burlington House, and picture entitled “Mariana in the South” at the New Gallery. It was to the last-named gallery that Mr Waterhouse sent a “Juliet” in the succeeding spring, his Royal Academy exhibits being two classic themes, namely “Flora and the Zephyrs” and “Ariadne”.

Of Mr Waterhouse’s subsequent work it is hardly necessary to speak. His style, settling in the early nineties into the more or less definite groove that we have all come to know it by, had not materially altered since. Hence we need no more than refer to Mr Waterhouse’s diploma picture “A Mermaid”, his “Nymphs finding the Head of Orpheus” (exhibited in 1901), or “Echo and Narcissus”, given to the world the following year. Other classic subjects include “Psyche opening the Golden Box”, “Boreas”8, and “Psyche opening the Door into Cupid’s Garden”. Of the few portraits executed by the late Academician we have left ourselves small space to speak. But they were not the happiest inspirations emanating from his hand. Of the half-dozen limned by the painter in late years, Mrs Schreiber, Miss Molly Rickman and Mrs Charles Newton Robinson are perhaps most familiar to the public.

NOTES

1 The profit from the Great Exhibition of 1851 was used to purchase land in South Kensington, where several museums were built, including the Natural History Museum and the forerunner of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

2 Waterhouse entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1871 as a sculptor. His sponsor was the artist FR Pickersgill, RA.

3 The Royal Academy is still located in Burlington House, Piccadilly. It was previously housed in the east wing of the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square (1836), and Somerset House (1780).

4 Every year, the Royal Academy’s Hanging Committee would select and arrange paintings for its Annual Exhibition. Pictures were hung frame-to-frame right up to the ceiling. This resulted in the best position being at eye level, or ‘on the line’.

5 Circe Invidiosa (Circe Poisoning the Sea) was later found to have been altered at the request of a buyer. Examples of other Circes from this period include Briton Riviere’s ‘Circe and her Swine’ and Hippolyte-Casimir Gourse’s ‘The Conversion of Ulysses’.

6 Danaë was stolen from its owners in 1947.

7 St. Cecilia was auctioned in June 2000 and set a new record-price for a Victorian painting (£6,603,750 UKP). The buyer was Lord Lloyd-Webber.

8 Boreas was lost for 90 years, re-appearing at auction in 1996.